![]()

Structure of the ADSPresentation at Archives and Reform - Preparing for Tomorrow, Australian Society of Archivists 1997 National Conference, Adelaide, 24- 26 July 1997.

We begin our presentation by looking at the structure of the ADS, not only its 'physical' or virtual structure, but also the conceptual framework, the idea and attitudes that drive and shape its development. With the advent of PCs and desktop database applications, ASAP began development of the ADS in 1991. To us, the PC revolution represented a considerable opportunity, and the way forward for archival documentation systems. The technology placed system development within reach, without the massive investment, overheads and specialist programming skills required by mainframe systems. At the same time though, archivists have been articulating the requirements of archival documentation systems for many years. Forced by the explosion in the amount of documentation produced by modern society and the pace and complexities of unrelenting change, archival methods and theory have been continually scrutinized. Here in Australia, pioneering work by Scott and Australian Archives in the sixties, focusing on the nature of records and the entities that created them, identified the 'relational' nature of archival documentation.[1] Sue McKemmish writes that what Scott identified was the need for:

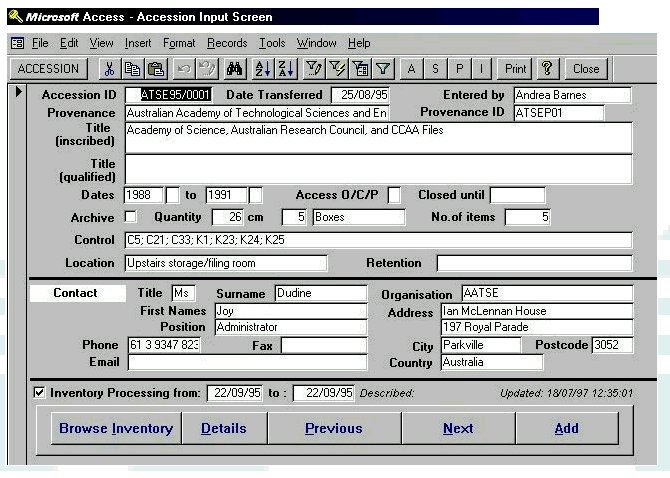

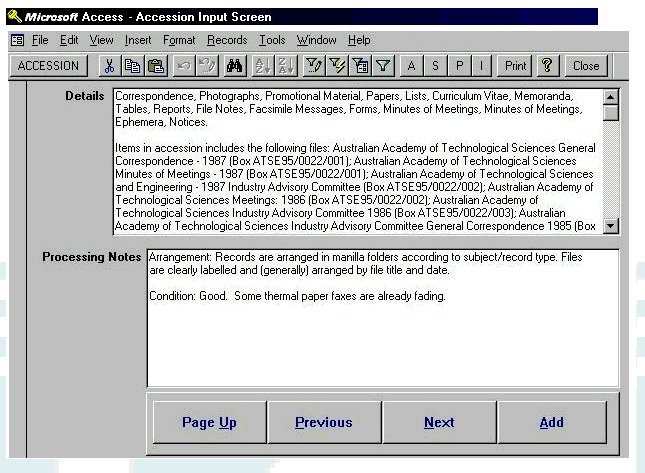

… a system capable of capturing and presenting archival data about the nature of the 'logical or virtual or multiple' relationships that exit at any moment of time (and hence through time) amongst records and between records and their contexts of creation and use.[2] In order to achieve this, it was necessary to document the context of records creation, i.e. provenance; document the records, i.e. series and inventory and then document the relationships between the two. And so the Australian 'Series' System was born. However it was born into a manual world. Compromises had to be made in order to stretch finite resources over an ever increasing volume of records. The focus had to be on macro appraisal and documentation. Presentation of archival data involved manual duplication of information and users had to be content with finding aids prepared primarily from the archivist's viewpoint. But now the computer technologists have caught up and we have relational database management applications, the tools to create the system Scott was searching for. With a computer database, the context, record or relationship needs only be documented once. It can then be used in any number of displays - screen, print copy, html and beyond. Fielded information rather then unwieldy slabs of text allow searching and grouping across attributes, so archivists and archives users have a myriad of access points and ways of selecting archival data to satisfy information needs. With technology we can move beyond the limitations of the manual world and take Scott's vision to the next level. Indeed many archivists, across the world are already articulating 'where to next', waiting for the next generation of information systems applications to come along so that we can deliver. This is a fundamental concept underpinning the development of the ADS. We must remain in contact with the cutting edge of technology, in order to deal with the records of tomorrow's world and to reap the benefits tomorrow's technology can bring into our own documentation systems. The Practical BaseThe ADS has also been shaped by the practical environment in which we operate. The decision to invest in systems development was as a practical solution to the limitations encountered out in our project work. Put simply - resources. Never enough time or money for extensive series, provenance and inventory description, on top of physical processing. Production of a finding aid, took more up more resources with long lead times to produce, publish and distribute. And what happened if more relevant records came to light in the meantime? So we turned to the computer systems. However it was not just a matter of automating existing processes. What dimension could technology bring to the process? How could we work more efficiently and effectively and make maximum use of limited resources? How could we improve the outcomes or in marketing jargon 'add more value'? I will not pretend that we came up with the answers overnight. Nor will I give you a detailed history of the trials and tribulations of the ADS system development. Indeed that development is ongoing. A mix of us working smarter, of harnessing the ever increasing sophistication of the application software and dealing with our clients ever increasing expectations and demands. Exciting stuff, as we test our methods, our systems and our ingenuity to ensure that records are preserved, maintaining their context, content and integrity and are made accessible to the people who need to use them. Reforming the ProcessSo how have we reformed the archival processing process? I'd like to say that we have sought to 'streamline' the process. But in today's world that often has negative connotations, implying loss of care for detail or reduced service and outputs. What we have done is look at what gaining physical and intellectual control involves and establishing a process which maximizes both, rather then doing one at the expense of the other. We have focused on systematic collection of data, rather then on creating any one particular output. Our philosophy has been that if you get the data in right then you should be able to do anything with it. So we start at where the records enter an archival records program - Accessioning. Our accessioning takes place where the records are currently located. We seek to document the records in situ, as found, as is before any appraisal or retention decisions are made. Accessioning to us, is in fact the process where information is gathered to make appraisal decisions. Hence while describing the records in the Accession table, we are also beginning to identify Series and Provenance entities. The beauty of the database is that we can create the appropriate description records in the appropriate tables, identify the relationships between them immediately and have them available for our own use in understanding a set of records. What information is collected in the accession table? Firstly each Accession is given a unique identifier, the Accession ID. For ease of identification down the track, the current container of the records is labeled with this id and a box, shelf or unit number. This labeling is quite useful. It shows that the records are part of a program, and may make people think twice before unauthorized moving, sorting or even destruction, but then again… |

|

|

Other information collected:

|

|

|

As part of the accessioning process, series and provenance entities can also be identified and established in the database. However the aim is not to write fully fledged and finely honed series and provenance descriptions at this stage. Merely to begin the identification process, capturing the information available from the records at hand, in the time at hand. Indeed, an accession may consist of more than one series, and a series may exist in more than one location and be part of many accessions. Reporting from the accession table can aid in this identification. The database system has the memory and the processing capabilities, to make some connections our tiny little brains cannot, BUT, and it is a big BUT, these capabilities can only be realised if the data is captured and interpreted in the right way. It's worth keeping in mind that computer maxim: garbage in, garbage out. Reforming InventorySo what happens at the end of accessioning? Well, the first point is that in a lot of cases accessioning never really ends. There will nearly always be more records. However, no matter what stage of the process, we can always add more records and quickly bring them under some physical and intellectual control wherever they may be, whatever state they may be in, by creating a new accession record. However, one can't accession forever, and there comes a time to move to the next stage, to begin the processing of the records and develop their intellectual control. Our aim is to move as quickly as possible to inventory processing utilizing the information gathered in the accession process to determine what that processing should be. The physical processing is an opportunity to capture contextual information about record creation, function and use. It is from the records themselves that we can learn about the entities that created, used and accumulated them, as well as the relationships amongst both them and the records. Thus our inventory table is a little more extensive then what you may be used to.

|

|

|

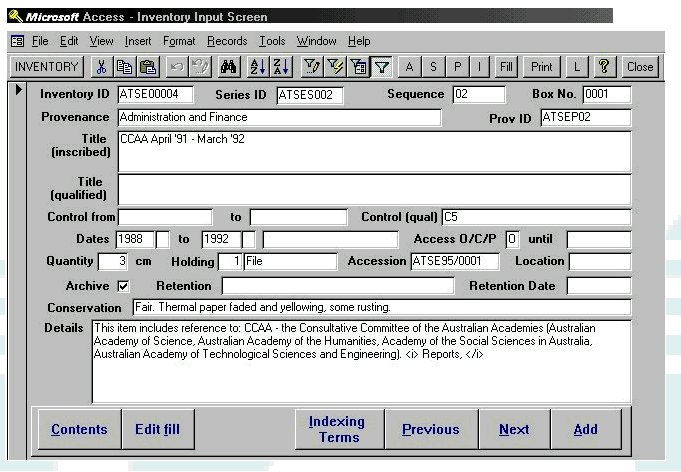

In the Inventory processing, each inventory item is give a unique identifier which is marked on the item and recorded in the database. Information describing content - titles and details, existing controls, date ranges, physical dimensions, conservation needs, formats - is input into the appropriate fields in the Inventory table. The item is linked to its organisational context by referencing it to:

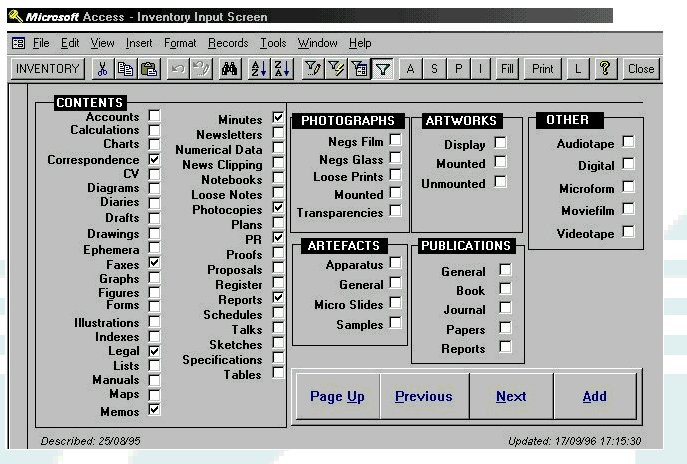

Record Formats of an inventory item are recorded by clicking on the appropriate check box.

|

|

|

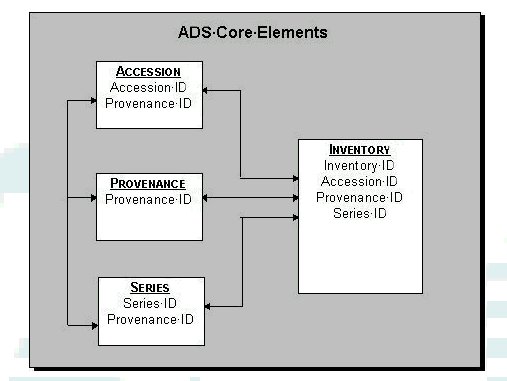

The level of inventory processing can be varied according to the structure, content and nature of the records and the amount of resources available. The Inventory item could be a file, a set of files, or even part of a file; a volume or set of volumes, an object, photograph, electronic record or larger groups of material that could be described under a single title. The detail of the series and provenance descriptions can be fleshed out from analysis of the inventory processing detail, augmented of course with information gathered from other sources, including annual reports, organisational charts, discussions with personnel etc. The idea is that all records identified in the accessioning process are documented at the series and inventory level. We aim to document the total records environment. Not only do the inventory, series and provenance tables contain archival documentation of records of continuing or long term value, but they also document other records created and used by an organisation or individual related to the surviving records, building a picture of the total recordkeeping environment. Varying the inventory unit ensures that high value records can be documented to a more detailed level then those of lesser value or those scheduled for destruction. In this way the ADS facilitates the systematic documentation of all records and what is done with them. Indeed strategic reporting from the system can manage the retention and disposal process. The ADSBut is that all there is to the ADS structure? Well no, but the accession, series, provenance and inventory tables and the relationships amongst and between them are the core elements and the basis on which its functionality depends.

|

|

|

The ADS has tables to manage physical location, loans and users; a variety of search interfaces for all types of users and a selection of report options to view the total collection or any parts of it. We have also developed customised modules to satisfy any particular requirements we, or our clients might have in managing or accessing records. Hence the ADS is not just an automated finding aid. It is an archival management information system. It is a processing tool. It documents records from the time they are identified as part of a records program, through to arrangement and physical location in an archival repository, and beyond to their subsequent use. It brings the many processing and finding aids archivists produce within the one integrated system. But how do our reforms aid in our ability to preserve records, maintaining content, context, structure and integrity ? Do they make the records accessible to the people who need to use them? I suggest you explore ADS In Practice and Beyond the ADS for some answers.

Notes

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

ASAPWeb |

Search |

Site Index |

Site Map

Top of page | ASAP Articles Home

Published by the Australian Science Archives Project on ASAPWeb,

August 1997.

|